Is US Pressure Against Foreign Digital Policy Working?

An Investigation of US Tariff Deal Priorities and Government Responses, including an Annex with Annotated Tariff Deal Texts.

.png)

An Investigation of US Tariff Deal Priorities and Government Responses, including an Annex with Annotated Tariff Deal Texts.

The US government’s pressure against digital policy is having an effect on the international and domestic level. Several governments have entered formal commitments on digital policy in “tariff deals” with the US. These deals, however, represent only the visible tip of the iceberg. The Digital Policy Alert (DPA) database reveals that governments are adapting their domestic digital policy even without deal commitments. A chilling effect, including governments pulling back their digital services taxes and adopting fewer restrictions on data flows, is emerging.

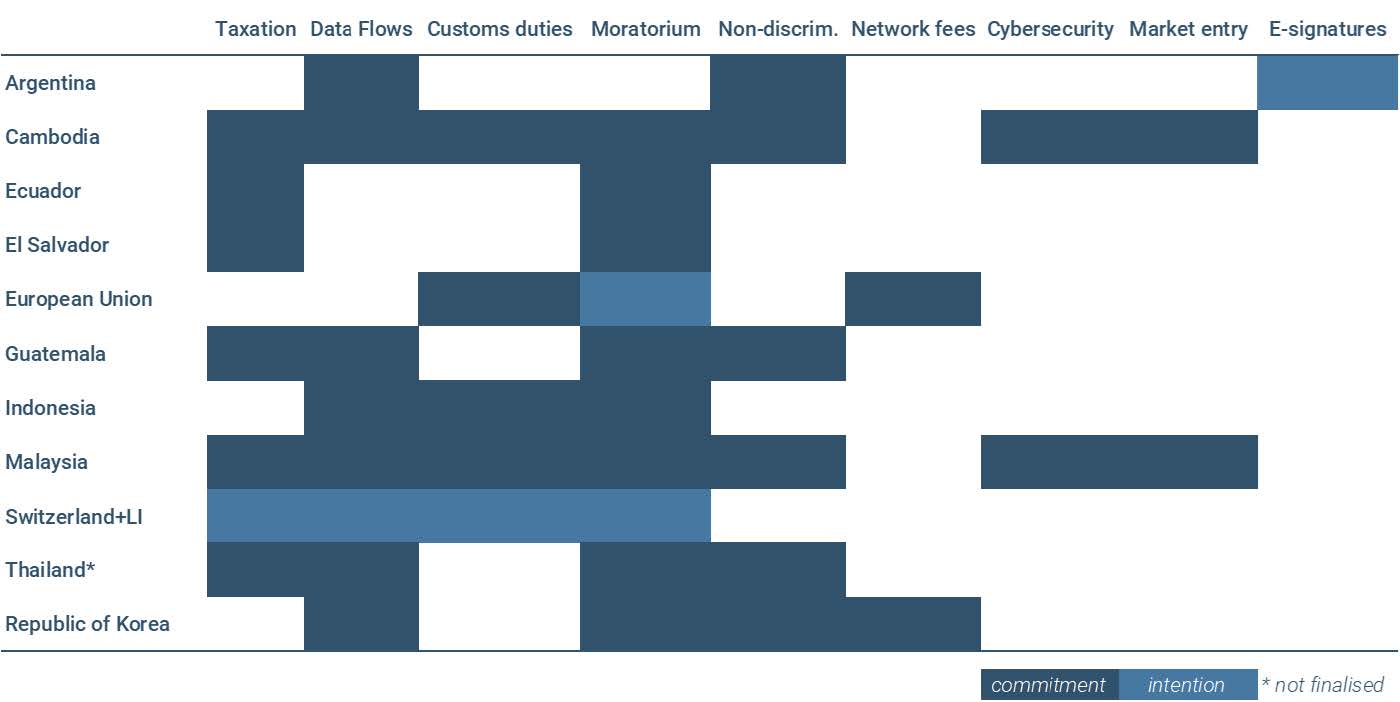

We investigate the effect of US pressure on both the international and domestic level. For the international level, we dissect all available “tariff deals” to identify commitments on digital policy. The overview below visualises these commitments, while the Annex provides all relevant text passages. For the domestic level, we leverage the DPA database to identify trends and concrete examples, without inferring causality. We compare global developments in the 8 months before the release of a US memorandum scrutinising foreign digital policy (2,428 DPA entries at the time of writing) to the 8 months after (2,328 DPA entries).

We analyse this effect across a broad spectrum of digital policy. We begin with an in-depth analysis for three types of digital policy that are top-of-mind for the US government: Digital services taxes, restrictions on cross-border data flows, and customs duties on electronic transmissions. Then, we outline five emerging digital policy commitments in tariff deals: non-discrimination, network usage fees, cybersecurity, market entry conditions, and electronic signatures. Next, we discuss four types of digital policy that we expect to arise in coming negotiations: local content promotion and rules regarding online content, competition, and AI. We conclude with three learnings for governments.

Figure 1: Digital policy commitments in tariff deals (see the complete text passages in the Annex).[1]

Figure 1 does not cover the Strategic Trade and Investment Agreements with Japan and the Republic of Korea, the Economic Prosperity Deal with the United Kingdom, the Technology Prosperity Deals with these three countries, and the Economic and Trade Deal with China. They are all covered in the text below and featured in the Annex.

Three US Priorities in Digital Policy

Digital services taxes (DSTs) are at the core of tensions in digital policy[2]. In the past years, Colombia, Kenya, Nigeria, and Malaysia, among others, joined Austria, France, Italy, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom in imposing such taxes.

The first Trump administration already scrutinised DSTs, investigating eleven DSTs and threatening tariffs on selected products against seven. The Biden administration then entered into transitional arrangements with foreign governments, which delayed the imposition of DSTs or credited payments against future tax obligations while the US government waived retaliatory tariffs. This occurred in view of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting to which 137 countries agreed in October 2021. The second Trump administration promptly withdrew from the Inclusive Framework and instructed the US Trade Representative to scrutinise DSTs again.

This pressure has had a clear effect on the international level: Seven deals include a commitment not to impose a DST, specifically those with Cambodia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Malaysia, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and Thailand. Their wording is quite consistent. Governments “refrain from” imposing or “shall not” impose digital services taxes that discriminate against US companies. The deal with Switzerland and Liechtenstein contains only an intention to continue not to impose DSTs and does not mention discrimination. Notably, the Economic Prosperity Deal with the United Kingdom does not cover its DST, which "remains unchanged” according to the press release.

The effect on the domestic level is striking. The DPA team documented less than half the amount of direct tax developments in the eight months after the memorandum was released compared to the eight months before. Several salient examples of governments pulling back or delaying their DSTs emerged throughout this year:

-

Canada rescinded its 3% DST in June to continue negotiations with the US.

-

Pakistan suspended its 5% Digital Presence Proceeds Tax for foreign firms in July.

-

Brazil reportedly delayed a DST bill due to trade negotiations, finally introducing it in July.

-

The French government is reportedly refraining from increasing its DST in the 2026 budget, as foreseen by a parliament vote in October, amid retaliation threats from US officials.

-

India removed its 6% Equalisation Levy on digital advertising in April, following the removal of its 2% levy on electronic commerce transactions in 2024.

Tensions concerning indirect taxes on the digital economy, such as value-added taxes (VAT), goods and services taxes, and sales taxes are less salient but also rising. The deals with Cambodia and Malaysia include commitments to not impose value-added taxes that discriminate against U.S. companies in law or in fact.

The US government has long opposed restrictions on data flows, including conditions for data transfers and data localisation requirements. It recently shifted its domestic and international stance on data flows. In July, it started restricting transfers of "bulk sensitive personal data and government-related data" to six "countries of concern", including China and Russia. In 2023, the US government withdrew its support for commitments regarding data transfers and data localisation under the WTO Joint Statement Initiative on Electronic Commerce.

Despite these shifts, the US government has pushed back against other governments’ data flow restrictions, with considerable impact on the international level: Eight deals include a commitment to free data flows, specifically those with Argentina, Cambodia, Guatemala, Malaysia, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and Thailand, and the joint fact sheet with the Republic of Korea. The wording consistently includes commitments to ensure the free transfer of data across trusted borders, although various deals contain unique language:

-

Argentina commits to recognise the US as an “adequate jurisdiction under Argentine law”.

-

Malaysia commits to data flows “with appropriate protections, for the conduct of business”.

-

The Republic of Korea commits to facilitate the transfer of “location, reinsurance, and personal data”.

-

Switzerland and Liechtenstein only formulate intentions, namely to facilitate trusted data flows and address data localisation requirements, taking into account legitimate public policy objectives, as well as to explore mechanisms that promote interoperability between privacy frameworks to facilitate secure data flows.

The effect is also present on the domestic level: The data flow restrictions documented by the DPA dropped by roughly a quarter in the 8 months after the memorandum’s release compared to the previous 8 months. The reduction was similar for data transfer conditions and data localisation obligations. Notably, binding developments, such as laws and regulations, and enforcement developments decreased more than non-binding guidance. One interpretation would be that US pressure influences not only the amount, but also the nature of restrictions on data flows.

Since 1998, a World Trade Organization moratorium prevents Members from imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions. Members have regularly renewed this moratorium during Ministerial Conferences, without ever making it permanent. At the 13th Ministerial Conference in 2024, members agreed that the moratorium would expire at the 14th Ministerial Conference in March 2026. This occurred due to growing concerns from developing countries regarding the erosion of their potential tariff revenue base.

Against this backdrop, the US government has successfully pursued two types of commitments on customs duties on the international level.

-

Ten deals contain a commitment to support a permanent moratorium at the WTO, specifically those with Cambodia, Ecuador, El Salvador, the European Union, Guatemala, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and Thailand. The language is very uniform, with two exceptions. Cambodia and Indonesia commit to support a moratorium immediately and unconditionally. The deals with the European Union and Switzerland and Liechtenstein only state intentions regarding the moratorium.

-

Five deals contain commitments not to impose customs duties on electronic transmissions, specifically those with Cambodia, the European Union, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Switzerland and Liechtenstein. Governments all commit to refrain from imposing or not to impose such customs duties, with some idiosyncrasies. Switzerland and Liechtenstein only formulate their intention. The deals with Cambodia and Malaysia specify that the commitment comprises content transmitted electronically. Indonesia commits to eliminate existing tariff lines on “intangible products” and suspend related requirements on import declarations.

Indonesia’s commitments stand out: It was a leading proponent of customs duties on electronic transmission and laid the groundwork for their imposition at the domestic level, without actually imposing them. Specifically, Indonesia subjects intangible goods to customs procedures. In 2006, Indonesia clarified that imports and exports by electronic means are covered by its customs regime. In 2018, Indonesia specified the types of intangible goods covered by its customs regime by expanding its import tariffs book with a chapter on software and other digital goods. In 2023, Indonesia implemented an import declaration procedure for software and other digital goods, requiring an import declaration within 30 days of payment. Its deal, however, contains commitments to reverse these changes.

Five Emerging Digital Policy Commitments

Emerging digital policy commitments in tariff deals cover non-discrimination, network usage fees, cybersecurity, market entry conditions, and electronic signatures.

Five deals contain non-discrimination[3] commitments, specifically those with Argentina, Cambodia, Guatemala, Malaysia, and the Republic of Korea. These governments commit to refrain from measures that discriminate against US companies, US digital services or US products distributed digitally. There are minimal differences in language, for instance the Republic of Korea commits to ensure that US companies are not discriminated against, while the deals with Argentina and Thailand refer to “digital products”. The deals do not specify what constitutes discrimination, although thresholds-based obligations could be considered to and non-discrimination is core to dispute settlement consultations against Canada’s DST under the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement.

Network usage fees are mentioned in two deals, with the European Union and the Republic of Korea. These fees would require digital service providers to pay internet service providers for the network capacity their high-traffic services consume. The EU has repeatedly considered such fees, most recently in its “fair share” consultation, without adopting them. The Republic of Korea maintains a unique “Sending Party Pays” framework on Internet traffic management, which does not mandate fees from digital service providers directly. Compensation has, however, been negotiated voluntarily and in litigation, and different bills to mandate fees have been introduced to the National Assembly. In the deal, the European Union “confirms that it will not adopt or maintain network usage fees". Meanwhile, the Republic of Korea commits to ensure that US companies do not face “unnecessary barriers in terms of laws and policies concerning digital services, including network usage fees”.

Cybersecurity is mentioned in two deals, with Cambodia and Malaysia. Cambodia commits to collaborate with the US to “address cybersecurity challenges”. Malaysia only commits to endeavour to collaborate with the United States to address cybersecurity challenges, along with other matters of mutual interest, such as information on threats and best practices.

The deals with Cambodia and Malaysia also contain commitments on market entry conditions. Cambodia commits not to require US persons to transfer or provide access to a “particular technology, production process, source code, or other proprietary knowledge” or to “purchase, utilize, or accord a preference to a particular technology” as a condition for doing business in Cambodia. The commitment foresees an exception for a Cambodian regulatory body or judicial authority demanding access to source code during a specific investigation, inspection examination, enforcement action, or judicial proceeding, with appropriate safeguards. The deal with Malaysia contains the same commitment with more extensive exceptions, including for commercial contracts, critical infrastructure, and government procurement.

Finally, the deal with Argentina includes a unique commitment on electronic signatures: Argentina intends to recognise electronic signatures that are valid under US law as valid under its own law.

Beyond non-discrimination, five deals contain commitments to address barriers impacting digital trade in general, specifically those with El Salvador, the European Union, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, and Thailand. Their language is consistent and, as with discrimination, does not specify what constitutes such barriers.

Four Digital Policy Commitments to Watch

Upcoming deals may well cover four types of digital policy which remain a priority for the US government, specifically rules on local content promotion, online content, competition, and AI.

Local content promotion refers to requirements for digital service providers to maintain quotas of local content, invest in local content productions, or compensate creators of digitally disseminated local content. Industry pushback against such requirements, including Australia's News Media and Digital Platforms Bargaining Code and Canada's Online News Act, has been vocal. The US government now also counters rules designed to "transfer significant funds" from US companies.

This pressure has had limited effect on the domestic level but not on the international level. Two deals contain language related to local content promotion. Thailand commits to “refrain from imposing screen quotas for film". The announcement of the deal with Malaysia mentions a commitment to refrain from requiring US social media platforms and cloud service providers to “pay into Malaysia's domestic fund". This language is not, however, present in the deal text itself. An example for the domestic effect is Australia's News Bargaining Incentive, which was reportedly paused in view of tensions, although a consultation was launched in November 2025.

Online content rules comprise both content moderation obligations, requiring platforms to remove certain content, and user speech rights, preventing platforms from removing certain content and facilitating redress. Domestically, the US government has adopted the TAKE IT DOWN Act, including content moderation obligations for non-consensual intimate imagery, and pursued enforcement on online content. Abroad, the US government has vocally countered online content rules, especially the European Union’s Digital Services Act. This pressure, exemplified by vice-president Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference, is based on a "free speech" narrative that does not acknowledge rules regarding user speech rights.

The effect on the international level is limited, while the domestic effect is visible. The only deal with language that could relate to online content rules is the Republic of Korea’s. It contains a passage on “laws and policies concerning digital services, including online platform regulations”. This seemingly refers to competition rules (see below). Meanwhile, the effect on the domestic level was visible in Switzerland’s draft platform regulation: It was published after a considerable delay because “more important things come first" during tariff negotiations.

The US government is pursuing enforcement action on competition in digital markets domestically, but countering foreign rules, especially in the European Union and the Republic of Korea. In February, the fact sheet accompanying the abovementioned memorandum announced scrutiny of the European Union’s Digital Markets Act. In August, the US president’s social media post decried “Digital Markets Regulations”, among others, before a visit from the president of the Republic of Korea. The US-Republic of Korea Digital Trade Enforcement Act, reintroduced in May, would authorise trade restrictions in reaction to digital competition rules.

The effect of this pressure is starting to appear on the domestic and international level.

-

On the international level, the Republic of Korea entered into a commitment to ensure that US companies do not face unnecessary barriers in terms of “laws and policies concerning digital services, including online platform regulations”. This unspecific wording seemingly refers to digital competition rules. In addition, the US government’s fact sheet stated that China will terminate antitrust and anti-monopoly investigations targeting US companies in the semiconductor supply chain. China, which is yet to confirm this, recently released preliminary findings that Nvidia’s acquisition of equity in Mellanox violated the Anti-Monopoly Law and opened an investigation into Qualcomm’s acquisition of Autotalks.

-

On the domestic level, China reportedly dropped a Google investigation during negotiations. The European Union, which did not enter a commitment, reportedly delayed several fines against US companies in view of trade tensions with the US, including fines against Google, for distorting competition in the advertising technology industry (EUR 2.95 billion), and against Apple and Meta, under the Digital Markets Act (EUR 500 million and EUR 200 million respectively). Notably, when these fines were issued, a US official declared them to be a “novel form of economic extortion” that “will not be tolerated” by the US.

Finally, the US government is pushing back against AI rules at home and abroad. Domestically, the Trump administration promptly rescinded Biden’s Executive Order on AI and later issued the AI Action Plan focused on accelerating AI innovation, building American AI infrastructure, and leading in international AI diplomacy and security. Currently, the US government is reportedly aiming to counter state-level AI rules, after an attempt to impose a moratorium on such rules failed during negotiations on the One Big Beautiful Bill. On the international stage, US officials are strongly opposing “excessive regulation” and the “European model of fear and overregulation”.

To date, the limited effect of this pressure is taking shape primarily on the international level, namely in Technology Prosperity Deals and Strategic Trade and Investment Deals. The Technology Prosperity Deals with both Japan and the Republic of Korea contain sections on accelerating AI adoption and innovation, with passages regarding the advancement of pro-innovation AI policy frameworks. The United Kingdom also negotiated a Technology Prosperity Deal, with the same language. Domestically, the United Kingdom reportedly delayed its AI law to align with the US. Japan’s Strategic Trade and Investment Deal includes a commitment to invest USD 550 billion, on projects to be selected by the US president, for instance in the AI and semiconductor sectors. The Republic of Korea’s Strategic Trade and Investment Deal is still being finalised, although a recent joint statement contains similar language, including references to AI and semiconductors.

Three Learnings for Governments

Governments with digital policies that cross with US interests should expect more pressure, learn from each other on the international level, and strategise on domestic implementation.

We expect more pressure from the US government for three reasons:

-

This pressure is not new per se, but unprecedentedly intense and broad. The US government has countered foreign digital policies affecting US companies for years, including in the US Trade Representative’s yearly National Trade Estimate report and investigations. This year, the intensity of the pressure is striking: Governments are already exposed to tariffs during negotiations and the US government’s narrative is harsher, framing digital policy as extortion and enforcement as taxation. The breadth of this pressure is equally unprecedented. The US “flood the zone” strategy pursues issue linkage across a broad spectrum of digital policy. It applies pressure not only to existing policy, but also to proposals and enforcement action. And it extends beyond tariff negotiations, for instance issuing visa restrictions for a Brazilian judge for alleged online “censorship”.

-

While causing turmoil, the pressure has brought successes on digital policy. Several of the abovementioned commitments concern contentious issues, including Indonesia’s stance on customs duties and the Republic of Korea’s stance on location data transfers. Furthermore, two deals empower the US government to wield influence in the future, complicating hedging strategies: Malaysia and Cambodia “shall consult” with the US before entering new digital trade agreements with other countries, that jeopardise essential US interests.

-

The US government continues expanding the pressure, including with governments who reached deals. The US Secretary of Commerce recently called for a rollback of digital rules in the European Union, which were not included in the tariff deal, to get a “cool steel and aluminium deal” and attract investment. The US Trade Representative has reportedly signaled that trade investigations would be launched if the Republic of Korea pursues digital regulations. Already, an ongoing trade investigation regarding Brazil scrutinises various digital policies, especially online content rules.

Governments can learn from each other on the international level, since the available deals reveal three insights. First, there is a pattern in the types of digital policy on which the US government is seeking commitments. Second, governments must not enter into commitments across all these types of digital policy to secure a deal, as evidenced by the growing patchwork of commitments. Third, commitments on the same type of digital policy vary in their bindingness and detail across different deals (see the Annex below). Governments can thus, for each type of digital policy, develop a position on whether to enter a commitment, of what kind, or to counter the pressure.

Having entered into commitments, governments currently strategise on domestic implementation. An agreement on the international level does not directly translate into an effect on the domestic level. Take the example of Malaysia’s 6% Service Tax on Digital Services, which generated revenues of MYR 1.6 billion (approx. USD 387 million) in 2024. The deal states that Malaysia “shall not impose digital services taxes, or similar taxes, that discriminate against U.S. companies in law or in fact”. The Malaysian Ministry of Investment, Trade and Industry’s Frequently Asked Questions document takes the position that “Malaysia does not agree to abolish the DST”, only to implement taxation fairly and without discrimination against US companies. Malaysia retains “full authority to impose digital taxes”. This stands in contrast to the strategy of governments who pulled back their DSTs on the domestic level, without getting a deal on the international level.

When faced with excessive pressure, governments could thus choose to enter international commitments, relieving pressure and buying time to develop creative solutions for domestic implementation.

Annex: Passages on Digital Policy in Global Tariff Deals

This Annex bundles text passages related to digital policy across available tariff deals:

Notably, these deals vary in legal nature and status.

-

For Cambodia and Malaysia we reference the agreements on reciprocal trade.

-

For Argentina, Ecuador, El Salvador, the European Union, Guatemala, Indonesia, Switzerland and Liechtenstein, and Thailand, we refer to joint statements.

-

For Japan, we cover the Memorandum of Understanding on Strategic Investments (see the fact sheet) and the Memorandum of Cooperation on the Technology Prosperity Deal.

-

For the Republic of Korea, we cover the joint fact sheet on the presidents’ meeting, the Memorandum of Understanding on Strategic Investments and the Memorandum of Cooperation on the Technology Prosperity Deal.

-

For the United Kingdom, we cover the General Terms for the Economic Prosperity Deal and the Memorandum of Understanding on the Technology Prosperity Deal.

-

For China, which has not yet confirmed language specific to digital policy, we provide punctual evidence based on the US fact sheet on the Deal on Economic and Trade.

-

We do not cover the joint statement with Viet Nam, since it states that digital trade commitments are yet to be finalised, and ongoing negotiations with no available joint language.

[Note that the PDF version of this report contains a color code to flag which passages related to which types of digital policy.]

Argentina

Argentina has committed to facilitating digital trade with the United States by recognizing the United States as an adequate jurisdiction under Argentine law for the cross-border transfer of data, including personal data; and by refraining from discrimination against U.S. digital services or digital products. Argentina also intends to recognize as valid under its law electronic signatures that are valid under U.S. law.

Ecuador

Ecuador has committed to facilitate digital trade, including through commitments to not impose digital service taxes that discriminate against U.S. companies and to support adoption of a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the WTO.

El Salvador

El Salvador has recommitted to preventing barriers to services and digital trade with the United States and committed to refrain from imposing discriminatory digital services taxes. The United States and El Salvador will support a permanent multilateral moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions.

European Union

The United States and the European Union commit to address unjustified digital trade barriers. In that respect, The European Union confirms that it will not adopt or maintain network usage fees. The United States and the European Union will not impose customs duties on electronic transmissions. The United States and the European Union intend to continue to support the multilateral moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the World Trade Organization and seek the adoption of a permanent multilateral commitment.

Guatemala

Guatemala has committed to facilitate digital trade, including by refraining from imposing digital services taxes or other measures that discriminate against U.S. digital services or U.S. products distributed digitally, ensuring the free transfer of data across trusted borders, and supporting a permanent multilateral moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Indonesia

Indonesia has committed to address barriers impacting digital trade, services, and investment. Indonesia will provide certainty regarding the ability to transfer personal data out of its territory to the United States. Indonesia has committed to eliminate existing HTS tariff lines on “intangible products” and suspend related requirements on import declarations; to support a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the WTO immediately and without conditions; and to take effective actions to implement the Joint Initiative on Services Domestic Regulation, including submitting its revised Specific Commitments for certification by the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Switzerland and Liechtenstein

Switzerland and Liechtenstein intend to continue to refrain from imposing digital services taxes.

The Participants intend to facilitate trusted cross-border data flows and address data localization requirements, taking into account legitimate public policy objectives.

The Participants intend to explore mechanisms that promote interoperability between their respective privacy frameworks with a view to facilitating secure cross-border transfers of data.

The Participants intend to refrain from imposing customs duties on electronic transmissions and to support the multilateral adoption of a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the WTO.

Thailand

The United States and Thailand will finalize commitments by Thailand to address barriers impacting digital trade, services, and investment. Thailand commits to refrain from imposing digital services taxes or measures that discriminate against U.S. digital services or digital products; to ensure the free transfer of data across trusted borders for the conduct of business; to support a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the WTO; to refrain from imposing screen quotas for film; to ease foreign ownership restrictions for U.S. investment in Thailand’s telecommunications sector; and to remove in-country processing requirements for all domestic retail electronic payment transactions for debit cards issued in Thailand.

China

China will terminate its various investigations targeting U.S. companies in the semiconductor supply chain, including its antitrust, anti-monopoly, and anti-dumping investigations.

Cambodia

Cambodia shall not impose digital services taxes, or similar taxes, that discriminate against U.S. companies, in law or in fact.

Cambodia shall facilitate digital trade with the United States, including by refraining from measures that discriminate against U.S. digital services or U.S. products distributed digitally, ensuring the free transfer of data across trusted borders for the conduct of business, and collaborating with the United States to address cybersecurity challenges.

Cambodia shall consult with the United States before entering into a new digital trade agreement with another country that jeopardizes essential U.S. interests.

Cambodia shall not impose any condition or enforce any undertaking requiring U.S. persons to transfer or provide access to a particular technology, production process, source code, or other proprietary knowledge, or to purchase, utilize, or accord a preference to a particular technology, as a condition for doing business in its territory. This article does not preclude a regulatory body or judicial authority of Cambodia from requiring a person of the United States to preserve and make available the source code of software, or an algorithm expressed in that source code, to the regulatory body or judicial authority for a specific investigation, inspection, examination, enforcement action, or judicial proceeding, subject to safeguards against unauthorized disclosure.

Cambodia shall not impose customs duties on electronic transmissions, including content transmitted electronically, and shall immediately and unconditionally support multilateral adoption of a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the WTO.

Malaysia

Malaysia shall not impose digital services taxes, or similar taxes, that discriminate against U.S. companies in law or in fact.

Malaysia shall facilitate digital trade with the United States, including by─

(a) refraining from measures that discriminate against U.S. digital services or U.S. products distributed digitally;

[Footnote 7: For greater certainty, Malaysia has the right to regulate in the public interest.]

(b) ensuring the cross-border transfer of data by electronic means across trusted borders, with appropriate protections, for the conduct of business; and

(c) endeavoring to collaborate with the United States to address cybersecurity challenges and matters of mutual interest, which may include exchanging information on threats and best practices, promoting the use of relevant international standards, and understanding capacity-building activities.

Malaysia shall consult with the United States before entering into a new digital trade agreement with another country that jeopardizes essential U.S. interests.

1. Malaysia shall not impose any condition or enforce any undertaking requiring U.S. persons to transfer or provide access to a particular technology, production process, source code, or other proprietary knowledge, or to purchase, utilize, or accord a preference to a particular technology, as a condition for doing business in its territory.

2. Nothing in this Article shall─

(a) preclude the inclusion or implementation of terms and conditions related to the provision of source code in commercially negotiated contracts;

(b) preclude a Party from requiring that access be provided to software used for critical infrastructure, to the extent required to ensure the effective functioning of critical infrastructure, subject to safeguards against unauthorized disclosure;

(c) preclude a Party from requiring the modification of source code of software necessary for that software to comply with laws or regulations which are not inconsistent with this Agreement;

(d) apply to government procurement;

(e) preclude a regulatory body or judicial authority of a Party from requiring a person of another Party to preserve and make available the source code of software, or an algorithm expressed in that source code, to the regulatory body for a specific investigation, inspection, examination, enforcement action, or judicial proceeding, subject to safeguards against unauthorized disclosure; or

(f) apply to a Party’s measures adopted or maintained for prudential reasons.[8]

[Footnote 8: For purposes of this paragraph, “non-confidential information” means information other than confidential information, and “confidential information” means information that relates to a specific enterprise and is protected under the laws and regulations of Malaysia.]

Each Party shall not impose customs duties on electronic transmissions, including content transmitted electronically, and shall support multilateral adoption of a permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the WTO. For greater certainty, this Article does not preclude a Party from imposing internal taxes, fees, or other charges on electronic transmissions, including content transmitted electronically, provided that those taxes, fees, or charges are imposed in a manner consistent with Articles I and III of the GATT 1994 or Articles II and XVII of the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

Japan

16. INVESTMENT SECTORS

Investments in the United States are intended to focus on sectors deemed to advance economic and national security interests, including but not limited to semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, metals, critical minerals, shipbuilding, energy (including pipelines), and artificial intelligence/quantum computing.

II. Areas of Cooperation

The Participants intend to collaborate in a number of disciplines, including but not limited to the following:

Accelerating AI Adoption and Innovation

AI promises a new Golden Age of Innovation by empowering individuals and supercharging progress across sectors like healthcare, biotechnology, and education. The Participants intend to collaborate closely on promoting pro-innovation AI policy frameworks, promoting exports across our full AI stack, ensuring the rigorous enforcement of existing protection measures while acknowledging the importance of strengthening such measures related to critical and emerging technologies, advancing shared work on industry standards, and safeguarding our children’s digital wellbeing, with a shared commitment to promoting a secure and trustworthy AI ecosystem in a mutually beneficial manner. Focus areas for collaboration are intended to include:

-

Driving innovative research to accelerate the application of AI for science, industry, and society through use-inspired initiatives supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, RIKEN, and other relevant research institutions and funders;

-

Deepening cooperation to advance high-performance computing, leading-edge semiconductor technologies, and quantum computing that underpin the AI era to enhance the foundational infrastructure essential for AI performance and applications;

-

Advancing pro-innovation AI policy frameworks and initiatives to support the adoption of a U.S. and Japan-led AI technology ecosystem;

-

Promoting exports across the full stack of U.S. and Japanese AI infrastructure, hardware, models, software, applications, and related standards;

-

Partnering to ensure the rigorous enforcement of existing protection measures, strengthen protection measures related to critical and sensitive technologies, and enhance supply chain resilience for the AI tech stack;

-

Promoting mutual understanding of guidelines and frameworks for AI development and adoption from the respective Participants, with the goal of harmonizing practices as applicable to encourage interoperability;

-

Advancing and refocusing the partnership between the U.S. Center for AI Standards and Innovation and the Japan AI Safety Institute towards a shared mission to promote AI innovation by fostering a secure and trustworthy AI ecosystem, including through working towards best practices in metrology for AI and industry standards development, improving understanding of both advanced AI models and sector-specific applications to drive continued AI adoption; and

-

Promoting education, innovation, and technology for children to flourish in the digital era and preparing future generations for the workplace of tomorrow.

Republic of Korea

The United States and the ROK commit to ensure that U.S. companies are not discriminated against and do not face unnecessary barriers in terms of laws and policies concerning digital services, including network usage fees and online platform regulations, and to facilitate cross-border transfer of data, including for location, reinsurance, and personal data. Further, the United States and the ROK will support the permanent moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions at the World Trade Organization.

19. INVESTMENT SECTORS

Investments in the United States are intended to focus on sectors deemed to advance economic and national security interests, including but not limited to shipbuilding, energy, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, critical minerals, and artificial intelligence/quantum computing.

II. Areas of Cooperation

The Participants aim to collaborate in a number of disciplines, including but not limited to the following:

Accelerating AI Adoption and Innovation

AI promises a new Golden Age of Innovation by empowering individuals and supercharging progress across sectors like healthcare, advanced manufacturing, and education. The Participants intend to collaborate closely on developing pro-innovation AI policy frameworks, promoting the export of trusted AI technology stacks, developing AI-ready datasets, strengthening the enforcement of technology protection measures, advancing shared work on industry standards, and fostering our children’s digital wellbeing. Focus areas for collaboration are intended to include:

-

Driving innovative research and development to accelerate the application of AI for science, advanced manufacturing, biotechnology, and related fields, including through use-inspired research opportunities, such as those supported through the U.S. National Science Foundation, the National Research Foundation of Korea, Institute of Information and Communication Technology Planning and Evaluation, and other relevant science funders;

-

Championing pro-innovation AI policy frameworks and efforts to support AI technology adoption;

-

Working together to promote U.S. and Korean AI exports across the full stack of AI hardware, models, software, applications, and standards;

-

Exploring collaboration on AI export deals across Asia and beyond to drive the adoption of a shared AI ecosystem in the region;

-

Partnering to strengthen the enforcement of existing AI compute protection measures and to discuss the alignment of protection measures for critical and emerging technologies;

-

Promoting mutual understanding of guidelines and frameworks for AI adoption from the respective Participants, to foster the harmonization of practices that encourage interoperability;

-

Collaborating to reduce operational burdens for innovators and technology companies, with particular attention to removing barriers to innovative, trusted, and privacy-preserving data hosting architectures, and ensuring a conducive environment for digital application platforms;

-

Advancing and refocusing the partnership between the U.S. Center for AI Standards and Innovation and the Korea AI Safety Institute towards a shared mission to promote secure AI innovation, including through working towards best practices in metrology for AI, industry standards development, and improving understanding of both advanced AI models and sector-specific applications to drive continued AI adoption; and

-

Engaging in discussions to promote education, innovation, and technology for children to flourish in the digital era and prepare future generations for the workplace of tomorrow, including by participating in the Fostering the Future Together global initiative established by First Lady Melania Trump.

United Kingdom

3. Increasing Digital Trade

(a) Both countries confirm that they will negotiate an ambitious set of digital trade provisions that will include within its scope services, including financial services.

(b) Both countries confirm that they will negotiate provisions on paperless trade, pre-arrival processing, and digitalized procedures for the movement of goods between our countries.

II. Areas of Cooperation

The Participants intend to collaborate in a number of disciplines, including but not limited to the following:

Accelerating AI Innovation

AI is the defining technology of our age, presenting limitless opportunities to improve people’s lives. The Participants intend to collaborate closely in the build-out of powerful AI infrastructure, facilitate research community access to compute, support the creation of new scientific data sets, and harness their expertise in metrology and evaluations to enable adoption and advance our collective security. The Participants intend to leverage this infrastructure and the AI expertise across industry and elsewhere, to deliver transformational AI-driven change for our societies and economies. Focus areas for collaboration are intended to include:

-

establishing joint Flagship Research programs between United States (U.S.) and United Kingdom (UK) science agencies, including the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health, the UK Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT), and the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and other relevant departments for AI-enabled science in joint priority areas, including collaborating on the development of models and datasets in mutual priorities such as AI for biotechnology, precision medicine including for cancer and rare and chronic diseases, and fusion energy, including through joint funding opportunities and the allocation of compute via existing peered processes through resources such as the U.S. National AI Research Resource and UK AI Research Resource;

-

advancing innovative research and development approaches to accelerate the application of AI for science, including automated labs and compute collaboration, including through an updated DSIT-DOE partnership and joint research opportunities supported through NSF, UKRI, and other relevant science funders;

-

catalyzing an AI for space partnership between the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the UK Space Agency, including developing AI models for space applications, supporting science and exploration missions, such as lunar and Martian foundational models;

-

advancing pro-innovation AI policy frameworks and efforts to support U.S. and UK-led AI technology adoption;

-

promoting U.S. and UK AI exports to offer the full stack of chips, data centers, and models;

-

exploring opportunities for collaboration in building secure AI infrastructure and supporting AI hardware innovation;

-

developing the workforce of the future and ensuring U.S. and UK citizens benefit from the opportunities of AI across the supply chain; and

-

advancing the partnership between the U.S. Center for AI Standards and Innovation and the UK AI Security Institute towards a shared mission to promote secure AI innovation, including through working towards best practices in metrology and standards development for AI models, improving understanding of the most advanced model capabilities, and exchanging talent between the Institutes.